The Divided Self

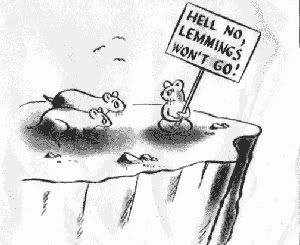

A quip of mine has come up a lot recently: that what is in one's objective national interest cannot be determined by a national polling. Or, to put it another, more direct way: just because you want to do X does not mean that X is in your objective self-interest. There are various examples I use to demonstrate this, such as a lemming wanting to run off a cliff or a mental patient wanting to bang their head against the wall. Clearly neither of these is in the individual's self-interest from an objective point of view, yet they believe otherwise and pursue their goal with vigour. Thus the quip offhandedly notes a truth that I see to be self-evident and indisputable, but it is also a truth that tells us much more than is currently appreciated.

The essence of the argument is that there are two types of self-interest, subjective and objective, and that the goal of the alliance should be to unite these as closely as possible. The subjective is simply one's opinion of what they should do -- run off a cliff or hit one's head against a wall, for example. The objective is what can be scientifically determined, and it is this that my work seeks to engage. The Slavery of International Rights, for example, pointed the objective desirability of an international anarchy over the then-popular subjective interest in an international legal system. Likewise The Meaning of Freedom outlined the objective desirability of freedom of potential over the still-popular subjective desirability of absolute freedom.

Sometimes these lead to counter-intuitive conclusions that people don't like -- how can rights be slavery and an Emperor be freedom -- and it is this gut reaction that epitomises the subjective interest. The conclusion is unbelievable not because of a scientific counter-argument but because it feels wrong. An absolute sovereign shouldn't be necessary for freedom, it goes against everything many individuals are taught from day zero.

This brings us to the elephant in the room, which asks us: why do so many, even those intellectuals who have considered the questions, hold subjective interests that are in contrast, or even contradictory to, their objective interests? It's a question that demands far more intensive study than can be provided here, but there are a number of points that we can touch on. The way that individuals enter alliances and the manner in which their material reality inside that alliance shapes their opinion is of primary importance. We can see, for example, the insanity particularly of the early days when nations were taught from birth to hate the Orders, and did so blindly without ever knowing anything about them. Moreover, here the individual and the alliance are caught in a feedback loop, with the alliance teaching the individual, which then becomes the alliance and teaches more individuals, perpetuating the cycle.

It is in these early days that the most basic of assumptions are implanted into the individual, and even after the more vulgar propaganda has begun to fall away, they are incredibly difficult to shake once they have been build into the very foundation of one's education. We can also recognise the passive role of base objective reality for keeping its distance from individuals in day to day life. That is to say, objective reality is not an obvious constant at the forefront of the mind. If one is finding oneself bombarded by propaganda, the sate of nature and all of its implications couldn't seem further away. And unfortunately reality won't come and punch you in the face to get your attention like it might in other worlds -- there are all manner of subjective interests pushed in front of the objective even in the most blatant of examples.

This all develops what one might call a 'false consciousness', where the subjective overrules the objective to the long-term detriment of the individual and the alliance. The Francoist can only hope to explain the objective interests beneath the subjective shell that is consumes us every second of every day. Unfortunately the Francoist can't make the horse drink.

6 Comments

Recommended Comments